Displaying dynamic content on a Pages static site

For many of our customers, a simple static site hosted on cloud.gov Pages is a lightweight and easy to manage solution for their agency or office. But what about situations where a static site needs to display a small amount of dynamic content; for example, structured data that updates more frequently than the written content, or is provided by another team or application? Certain kinds of data and content are more suitably stored in a database and accessed via an API on page load. While those services aren’t available in Pages, databases and APIs are available to our customers through cloud.gov.

Taking advantage of end-to-end cloud.gov services gives our agency customers baked-in security to help ease their compliance burden, and we provide support for dual agreements to make accessing these services simple. Below, we share how to display dynamic content using a lightweight database and API on cloud.gov connected to a Pages static website. Once you see how easy it is, we hope you’ll consider situations where your static Pages sites could be enhanced with dynamic content using additional cloud.gov services.

What you’ll need to get started

-

Some data you need to store, process, or access separately from the static site. In this case, we pulled a CSV file dataset from the FDIC, a Pages customer, which is hosted on data.gov, another office alongside cloud.gov in TTS.

-

A database and environment to store the data, provided by cloud.gov. In our example, we chose an RDS instance(Relational Database Service) of the PostgreSQL v15 database due to its rich feature set and simple methods of storing data from a CSV.

-

A server-side application that securely accesses the database and responds to HTTP requests. Our example uses a simple API flask application deployed on cloud.gov

-

The static website hosted on cloud.gov Pages. Our example uses a simple HTML file, but you could use any static site generator or single-page application on Pages.

How it all comes together

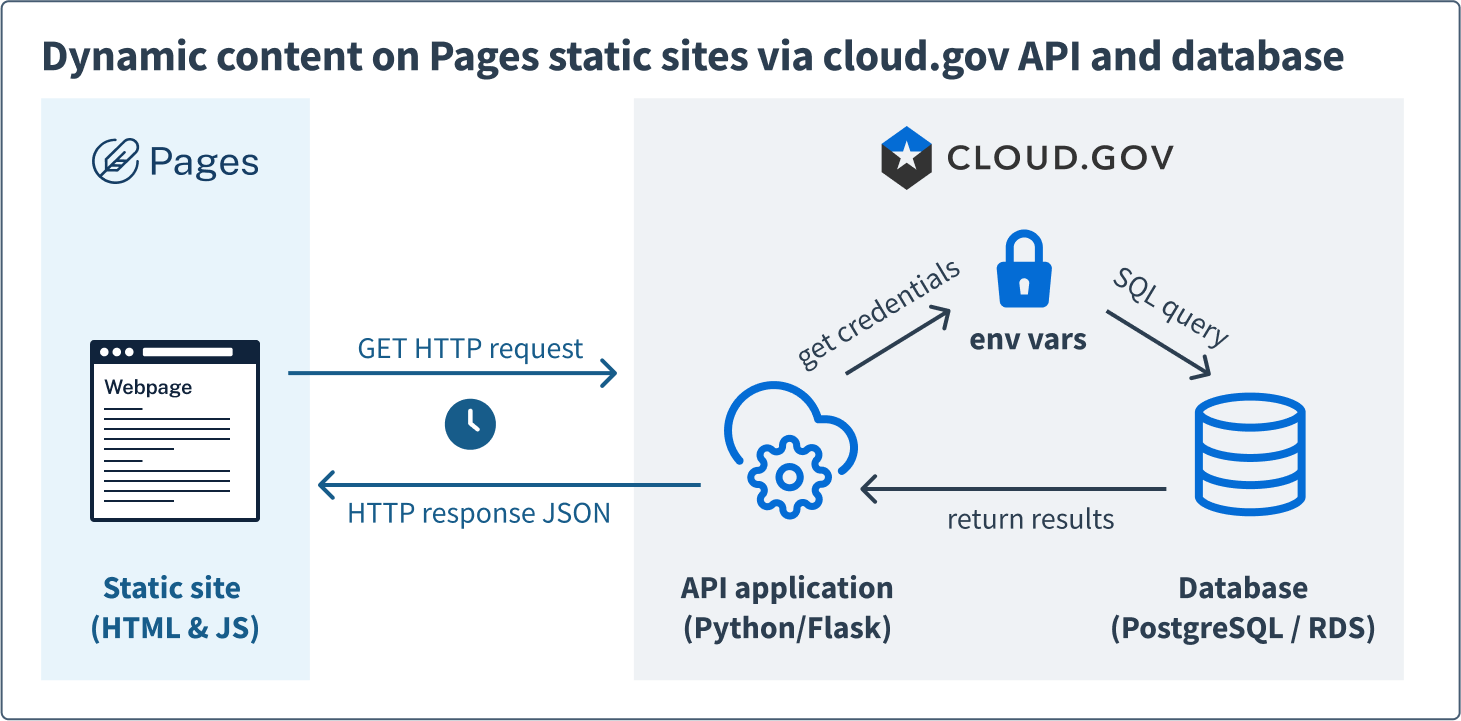

The below diagram shows the relationships between the three services:

-

The PostgreSQL database, which houses the dataset and returns the results found by the query. The fetched data is sent back to the API application, and the API application passes it on to the static site in the response body as JSON.

-

The API application first securely connects to the database by retrieving the RDS service credentials via cloud.gov’s Cloud Foundry environment. Once it establishes a secure connection to the PostgreSQL database, the application executes a SQL query against the database.

-

The static website, hosted on Pages, makes an HTTP

fetchrequest for some dynamic content to the cloud.gov-hosted API application.

Set up a database using cloud.gov’s RDS

Before you can create an API to access the data, the data must be available in the appropriate cloud.gov org and space. It’s relatively straightforward to provision a database of your choice and make it available for querying from other applications using cloud.gov’s RDS.

When you create an RDS service instance, cloud.gov automatically creates the default username and password for the database. If you want to allow an application (like our Flask API app) to access that database, you can bind that RDS database service to your application to safely expose those credentials as environment variables within the cloud.gov environment. This means your cloud.gov API application will have privileges to data that your Pages app will not, which can be useful in separating data concerns and keeping some information private.

In our case, we provisioned a PostgreSQL v15 database instance within cloud.gov to store some sample data. For the purposes of filling out an example database, we sourced a CSV from FDIC which itemizes recently failed banks, and then imported the CSV into the database’s single row table using the syntax COPY/FROM.

When queried via the API application, the database will select a number of rows, convert them to a Python dictionary via the RealDictCursor module, and return that collection.

Bank Name | City | State | Cert | Acquiring Institution | Closing Date | Fund | id

-------------------------+---------------+-------+-------+-------------------------------------+--------------+-------+---

Citizens Bank | Sac City | IA | 8758 | Iowa Trust & Savings Bank | 3-Nov-23 | 10545 | 1

Heartland Tri-State Bank | Elkhart | KS | 25851 | Dream First Bank, N.A. | 28-Jul-23 | 10544 | 2

First Republic Bank | San Francisco | CA | 59017 | JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. | 1-May-23 | 10543 | 3

Signature Bank | New York | NY | 57053 | Flagstar Bank, N.A. | 12-Mar-23 | 10540 | 4

Silicon Valley Bank | Santa Clara | CA | 24735 | First–Citizens Bank & Trust Company | 10-Mar-23 | 10539 | 5

If you’re thinking of trying this yourself, know that you aren’t limited to using RDS and PostgreSQL for storing the data; you have your choice of database infrastructure hosted on cloud.gov. Check out more options for database services provided by cloud.gov in our CloudFoundry marketplace. Please note that database options are limited for those working in a cloud.gov sandbox.

Set up a server API Application in your cloud.gov org space

You may write the server-side API in whatever language you’re comfortable with; we chose a simple Flask application in Python. Our example app which is hosted on cloud.gov serves as the interface between the PostgreSQL database and the Pages website. Through the Flask application’s endpoint, the Pages website can request data and receive structured responses via HTTP. In our example app, the Flask app fetches the 15 most recent results from the PostgreSQL database table and returns them via HTTP as an JSON response. JSON is a reliable choice for easy parsing from the front-end static site using JavaScript, but you could also send XML, a string, or another data type.

1. Import the modules

In order for our example web server to handle HTTP requests, dispatch responses, and interact with the database and environment, we needed a handful of Python modules:

- flask for creating the web server and preparing the JSON response

- os for reading environment variables and returning the result

- cfenv for interacting with Cloud Foundry environment variables

- psycopg2 and psycopg2.extras for interacting with PostgreSQL database and running queries

- RealDictCursor for fetching database results as dictionaries

- flask_cors and CORS for handling Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS), which is what allows Pages and the server to talk to one another even though they’re on separate domains

2. Set up the secure database connection

Because we’ve set up the database using RDS and bound to the service in this cloud.gov org space, we have direct access to the database credentials via application environment variables. Cloud.gov and RDS make it easy to set up a secure connection to the database using these environment variables. Here is how we connect to our database using the psycopg2 Python module in our Flask app:

aws_rds = app_env.get_service(name='your-database-name-here')

connection = psycopg2.connect(

host=aws_rds.credentials.get('host'),

user=aws_rds.credentials.get('username'),

password=aws_rds.credentials.get('password'),

database=aws_rds.credentials.get('name'),

port=aws_rds.credentials.get('port'),

)

3. Define the routes

The server application can now access the database, so we need it to provide endpoints for our static site to actually make the requests. These endpoints are defined in the Flask application’s routes. Our example app has two endpoints that can handle GET requests.

-

The root-level route (

"/") is accessed when an HTTP request is made to the bare domain itself; in our case, it will react to requests of https://cfpyapi.app.cloud.gov/ with a simple string response letting you know the app is running. It’s a best practice not to use your root-level domain for serving data anything other than some general information about your API service. -

The second route (

"/get_table") is the one we use for accessing data from the database. When an HTTP request visits https://cfpyapi.app.cloud.gov/get_table, the Flask app will execute ourget_table()function, which queries the database using the above credentials, finds matching results, and returns them in JSON format. Serving data and handling requests from a route endpoint makes the API more organized and easier to understand. When you need more endpoints for other queries in the future, it’s easy to add more routes.

@app.route('/', methods=['GET'])

def hello():

return 'There is a table right behind this door!'

@app.route('/get_table', methods=['GET'])

def get_table(page):

cursor = connection.cursor(cursor_factory=RealDictCursor)

4. Make the API available to your Pages app

By default, a Flask web server like ours handles HTTP requests, executes the queries, and sends back JSON responses to the client, as long as the request comes from the same origin (or domain). The initial CORS settings assume you would not want websites and applications from other domains to be able to make requests of yours. In order for the app to respond to a request from a static site, that request origin must be specifically allowed in the CORS settings. It’s good security practice to use environment variables whenever you’re able to so we’ve stored our Pages website URL as an environment variable in the application instance using cf push --var ORIGIN='<site>.sites.pages.cloud.gov'.This not only enables us to avoid having to hardcode the full URL but also if we had different environments ie. development, staging and production we can easily change the origin without having to modify the code. If your Pages site uses a custom domain, that would be the origin to use.

origin = os.getenv("ORIGIN")

port = int(os.getenv("PORT", 8080))

app = Flask(__name__)

CORS(app, origins=origin)

Once your server API can connect to the database, execute queries at specific routes, and respond to only your Pages site domain, you’re ready to deploy. For instructions on how to deploy applications on cloud.gov, please refer to the official cloud.gov documentation.

Serve content to the Pages website

Now, you’re ready to request dynamic content from your static site. In our example, the Pages-hosted site is a single index.html file with some CSS and image assets and a few lines of JavaScript to make the request and display the dynamic content. We’re using an already minified version of the U.S. Web Design System (USWDS) library from a Content Delivery Network (CDN) so there are no build tasks, transpiling, preprocessing, or compiling in this project – just a simple static site with some nav and the basic structure of a table, waiting to be filled with dynamic content.

There are two steps left: Making the HTTP request to the server app, and then displaying the response that the server app provides. Both are handled with straightforward JavaScript.

1. Make the request

First, our static site makes an asynchronous request to the API. There are a few ways to do this; our example function getDataFromCloudAPI() uses the fetch pattern to make a request at the /get_table endpoint, waits for the response using await, and then parses it into JSON when the Promise resolves. We’ve wrapped the request in a try/catch block to log any errors to the console in the browser if the request fails. Once resolved, the function ultimately returns the data requested in JSON.

async function getDataFromCloudAPI() {

let dataJson = null;

try {

const response = await fetch("https://cfpyapi.app.cloud.gov/get_table");

dataJson = await response.json();

} catch (error) {

console.log(error)

}

finally {

return dataJson;

}

}

2. Display the dynamic content

To keep our example simple, our static site displays the API-provided data in a simple HTML table. Using the JSON response data, we first build the table’s headers and then the rows, one by one, and append them all to an empty HTML table element that already exists in the static page. Using the source data to build both the table headers and the content rows means they will always match, even if the data structure on the server or database changes.

function createTableHead(rowData) {

const tableHead = document.createElement("thead");

let newRow = tableHead.insertRow();

Object.entries(rowData[0]).forEach(([key, value], cellIndex) => {

if (key !== "id") {

let newHeader = document.createElement('th');

newHeader.innerHTML = key;

newRow.appendChild(newHeader);

}

});

return tableHead

}

function createTableBody(rowData) {

const tableBody = document.createElement("tbody");

rowData.forEach((row, rowIndex) => {

let newRow = tableBody.insertRow(rowIndex);

Object.entries(row).forEach(([key, value], cellIndex) => {

if (key !== "id") {

let newCell = newRow.insertCell(cellIndex)

newCell.innerHTML = value;

}

});

});

return tableBody

}

function createTable(data) {

document.getElementById("data-table").appendChild(createTableHead(data));

document.getElementById("data-table").appendChild(createTableBody(data));

}

And that’s it! The static HTML page makes the fetch request to the API on load, then builds the table contents using the response, seamlessly.

Serving dynamic content from a backend database via an API to a static site hosted on cloud.gov Pages is easy within the cloud.gov ecosystem. We proudly offer a suite of secure and compliant databases which you can leverage to store data and dynamically display within their Pages websites without the need to manually update the static files or struggle with large data collections checked into the static site repo.

If you’re interested in enhancing your static sites with dynamic content, we’d love to help you set up a dual agreement for cloud.gov and Pages services with your agency or office. If you’re already a Pages customer, it takes a simple modification to your current IAA to access services from cloud.gov to get started. Launching an app on cloud.gov will require an Authority to Operate (ATO), and we’re here to help you through every stage. For more information, please reach out to inquiries@cloud.gov.

For support with implementation and general questions about Pages sites, please reach out to pages-support@cloud.gov.